The principles listed below are the result of long-term research studies on the origins of drug abuse behaviors and the common elements of effective prevention programs. These principles were developed to help prevention practitioners use the results of prevention research to address drug use among children, adolescents, and young adults in communities across the country. Parents, educators, and community leaders can use these principles to help guide their thinking, planning, selection, and delivery of drug abuse prevention programs at the community level.

Prevention programs are generally designed for use in a particular setting, such as at home, at school, or within the community, but can be adapted for use in several settings. In addition, programs are also designed with the intended audience in mind: for everyone in the population, for those at greater risk, and for those already involved with drugs or other problem behaviors. Some programs can be geared for more than one audience.

NIDA's prevention research program focuses on risks for drug abuse and other problem behaviors that occur throughout a child's development, from pregnancy through young adulthood. Research funded by NIDA and other Federal research organizations - such as the National Institute of Mental Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - shows that early intervention can prevent many adolescent risk behaviors.

Principle 1 - Prevention programs should enhance protective factors and reverse or reduce risk factors (Hawkins et al. 2002).

-

The risk of becoming a drug abuser involves the relationship among the number and type of risk factors (e.g., deviant attitudes and behaviors) and protective factors (e.g., parental support) (Wills et al. 1996).

-

The potential impact of specific risk and protective factors changes with age. For example, risk factors within the family have greater impact on a younger child, while association with drug-abusing peers may be a more significant risk factor for an adolescent (Gerstein and Green 1993; Dishion et al. 1999).

-

Early intervention with risk factors (e.g., aggressive behavior and poor self-control) often has a greater impact than later intervention by changing a child's life path (trajectory) away from problems and toward positive behaviors (Ialongo et al. 2001; Hawkins et al. 2008).

-

While risk and protective factors can affect people of all groups, these factors can have a different effect depending on a person's age, gender, ethnicity, culture, and environment (Beauvais et al. 1996; Moon et al. 1999).

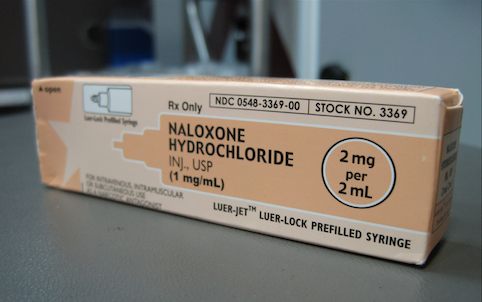

Principle 2 - Prevention programs should address all forms of drug abuse, alone or in combination, including the underage use of legal drugs (e.g., tobacco or alcohol); the use of illegal drugs (e.g., marijuana or heroin); and the inappropriate use of legally obtained substances (e.g., inhalants), prescription medications, or over-the-counter drugs (Johnston et al. 2002).

Principle 3 - Prevention programs should address the type of drug abuse problem in the local community, target modifiable risk factors, and strengthen identified protective factors (Hawkins et al. 2002).

Principle 4 - Prevention programs should be tailored to address risks specific to population or audience characteristics, such as age, gender, and ethnicity, to improve program effectiveness (Oetting et al. 1997; Olds et al. 1998; Fisher et al. 2007; Brody et al. 2008).

Principle 5 - Family-based prevention programs should enhance family bonding and relationships and include parenting skills; practice in developing, discussing, and enforcing family policies on substance abuse; and training in drug education and information (Ashery et al. 1998).

Family bonding is the bedrock of the relationship between parents and children. Bonding can be strengthened through skills training on parent supportiveness of children, parent-child communication, and parental involvement (Kosterman et al. 1997; Spoth et al. 2004).

Parental monitoring and supervision are critical for drug abuse prevention. These skills can be enhanced with training on rule-setting; techniques for monitoring activities; praise for appropriate behavior; and moderate, consistent discipline that enforces defined family rules (Kosterman et al. 2001).

Drug education and information for parents or caregivers reinforces what children are learning about the harmful effects of drugs and opens opportunities for family discussions about the abuse of legal and illegal substances (Bauman et al. 2001).

Brief, family-focused interventions for the general population can positively change specific parenting behavior that can reduce later risks of drug abuse (Spoth et al. 2002b).

Principle 6 - Prevention programs can be designed to intervene as early as infancy to address risk factors for drug abuse, such as aggressive behavior, poor social skills, and academic difficulties (Webster-Stratton 1998; Olds et al. 1998; Webster-Stratton et al. 2001; Fisher et al. 2007).

Principle 7 - Prevention programs for elementary school children should target improving academic and social-emotional learning to address risk factors for drug abuse, such as early aggression, academic failure, and school dropout. Education should focus on the following skills (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2002; Ialongo et al. 2001; Riggs et al. 2006; Kellam et al. 2008; Beets et al. 2009):

-

self-control;

-

emotional awareness;

-

communication;

-

social problem-solving; and

-

academic support, especially in reading.

Principle 8 - Prevention programs for middle or junior high and high school students should increase academic and social competence with the following skills (Botvin et al. 1995; Scheier et al. 1999; Eisen et al. 2003; Ellickson et al. 2003; Haggerty et al. 2007):

-

study habits and academic support;

-

communication;

-

peer relationships;

-

self-efficacy and assertiveness;

-

drug resistance skills;

-

reinforcement of anti-drug attitudes; and

-

strengthening of personal commitments against drug abuse.

Principle 9 - Prevention programs aimed at general populations at key transition points, such as the transition to middle school, can produce beneficial effects even among high-risk families and children. Such interventions do not single out risk populations and, therefore, reduce labeling and promote bonding to school and community (Botvin et al. 1995; Dishion et al. 2002; Institute of Medicine 2009).

Principle 10 - Community prevention programs that combine two or more effective programs, such as family-based and school-based programs, can be more effective than a single program alone (Battistich et al. 1997; Spoth et al. 2002c; Stormshak et al. 2005).

Principle 11 - Community prevention programs reaching populations in multiple settings - for example, schools, clubs, faith-based organizations, and the media - are most effective when they present consistent, community-wide messages in each setting (Chou et al. 1998; Hawkins et al. 2009).

Principle 12 - When communities adapt programs to match their needs, community norms, or differing cultural requirements, they should retain core elements of the original research-based intervention (Spoth et al. 2002b; Hawkins et al. 2009), which include:

-

Structure (how the program is organized and constructed);

-

Content (the information, skills, and strategies of the program); and

-

Delivery (how the program is adapted, implemented, and evaluated).

Principle 13 - Prevention programs should be long-term with repeated interventions (i.e., booster programs) to reinforce the original prevention goals. Research shows that the benefits from middle school prevention programs diminish without followup programs in high school (Botvin et al. 1995; Scheier et al. 1999).

Principle 14 - Prevention programs should include teacher training on good classroom management practices, such as rewarding appropriate student behavior. Such techniques help to foster students' positive behavior, achievement, academic motivation, and school bonding (Ialongo et al. 2001; Kellam et al. 2008).

Principle 15 - Prevention programs are most effective when they employ interactive techniques, such as peer discussion groups and parent role-playing, that allow for active involvement in learning about drug abuse and reinforcing skills (Botvin et al. 1995).

Principle 16 - Research-based prevention programs can be cost-effective. Similar to earlier research, recent research shows that for each dollar invested in prevention, a savings of up to $10 in treatment for alcohol or other substance abuse can be seen (Aos et al. 2001; Hawkins et al. 1999; Pentz 1998; Spoth et al. 2002a; Jones et al. 2008; Foster et al. 2007; Miller and Hendrie 2009).

References

-

Aos, S.; Phipps, P.; Barnoski, R.; and Lieb, R. The Comparative Costs and Benefits of Programs to Reduce Crime. Vol. 4 (1-05-1201).Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, May 2001.

-

Ashery, R.S.; Robertson, E.B.; and Kumpfer, K.L., eds. Drug Abuse Prevention Through Family Interventions. NIDA Research Monograph No. 177. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998.

-

Battistich, V.; Solomon, D.; Watson, M.; and Schaps, E. Caring school communities. Educ Psychol 32(3):137-151, 1997.

-

Bauman, K.E.; Foshee, V.A.; Ennett, S.T.; Pemberton, M.; Hicks, K.A.; King, T.S.; and Koch, G.G. The influence of a family program on adolescent tobacco and alcohol. Am J Public Health 91(4):604-610, 2001.

-

Beauvais, F.; Chavez, E.; Oetting, E.; Deffenbacher, J.; and Cornell, G. Drug use, violence, and victimization among White American, Mexican American, and American Indian dropouts, students with academic problems, and students in good academic standing. J Couns Psychol 43:292-299, 1996.

-

Beets, M.W.; Flay, B.R.; Vuchinich, S.; Snyder, F.J.; Acock, A.; Li, K-K.; Burns, K.; Washburn, I.J.; and Durlak, J. Use of a social and character development program to prevent substance use, violent behaviors, and sexual activity among elementary-school students in Hawaii. Am J Public Health 99(8):1438-1445, 2009.

-

Botvin, G.; Baker, E.; Dusenbury, L.; Botvin, E.; and Diaz, T. Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug-abuse prevention trial in a white middle class population. JAMA 273:1106-1112, 1995.

-

Brody, G.H.; Kogan, S.M.; Chen, Y.-F.; and Murry, V.M. Long-Term Effects of the Strong African American Families Program on youths' conduct problems. J Adolesc Health 43:474-481, 2008.

-

Chou, C.; Montgomery, S.; Pentz, M.; Rohrbach, L.; Johnson, C.; Flay, B.; and Mackinnon, D. Effects of a community-based prevention program in decreasing drug use in high-risk adolescents. Am J Public Health 88:944-948, 1998.

-

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Predictor variables associated with positive Fast Track outcomes at the end of third grade. J Abnorm Child Psychol 30(1):37-52, 2002.

-

Dishion, T.; McCord, J.; and Poulin, F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol 54:755-764, 1999.

-

Dishion, T.; Kavanagh, K.; Schneiger, A.K.J.; Nelson, S.; and Kaufman, N. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family centered strategy for the public middle school. Prev Sci 3(3):191-202, 2002.

-

Eisen, M.; Zellman, G.L.; and Murray, D.M. Evaluating the Lions-Quest "Skills for Adolescence" drug education program: Second-year behavior outcomes. Addict Behav 28(5):883-897, 2003.

-

Ellickson, P.L.; McCaffrey, D.F.; Ghosh-Dastidar, B.; and Longshore, D. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a large-scale trial of project ALERT in middle schools. Am J Public Health 93(11):1830-1836, 2003.

-

Fisher, P.A.; Stoolmiller, M.; Gunnar, M.R.; and Burraston, B.O. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32(8-10):892-905, 2007.

-

Foster, E.M.; Olchowski, A.E.; and Webster-Stratton, C.H. Is stacking intervention components cost-effective? An analysis of the Incredible Years Program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46(11):1414-1424, 2007.

-

Gerstein, D.R., and Green, L.W., eds. Preventing drug abuse: What do we know? Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1993.

-

Haggerty, K.P.; Skinner, M.L.; MacKenzie, E.P.; and Catalano, R.F.A. Randomized trial of parents who care: Effects on key outcomes at 24-month follow-up. Prev Sci 8:249-260, 2007.

-

Hawkins, J.D.; Catalano, R.F.; Kosterman, R.; Abbott, R.; and Hill, K.G. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 153:226-234, 1999.

-

Hawkins, J.D.; Catalano, R.F.; and Arthur, M. Promoting science-based prevention in communities. Addict Behav 27(6):951-976, 2002.

-

Hawkins, J.D.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.; Hill, K.G.; and Abbott, R.D. Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162(12):1133-1141, 2008.

-

Hawkins, J.D.; Oesterle, S.; Brown, E.C.; Arthur, M.W.; Abbott, R.D.; Fagan, A.A.; and Catalano, R. Results of a type 2 translational research trial to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency: A test of communities that care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163(9):789-798, 2009.

-

Ialongo, N.; Poduska, J.; Werthamer, L.; and Kellam, S. The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. J Emot Behav Disord 9:146-160, 2001.

-

Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. National Academies Press, Washington DC, 2009.

-

Johnston, L.D.; O'Malley, P.M.; and Bachman, J.G. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2002. Volume 1: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2002.

-

Jones, D.E.; Foster, E.M.; and Group, C.P. Service use patterns for adolescents with ADHD and comorbid conduct disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res 36(4):436-449, 2008.

-

Kellam, S.G.; Brown, C.H.; Poduska, J.; Ialongo, N.; Wang, W.; Toyinbo, P.; Petras, H.; Ford, C.; Windham, A.; and Wilcox, H.C. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 95 (Suppl 1):S5-S28, 2008.

-

Kosterman, R.; Hawkins, J.D.; Spoth, R.; Haggerty, K.P.; and Zhu, K. Effects of a preventive parent-training intervention on observed family interactions: Proximal outcomes from preparing for the drug free years. J Community Psychol 25(4):337-352, 1997.

-

Kosterman, R.; Hawkins, J.D.; Haggerty, K.P.; Spoth, R.; and Redmond, C. Preparing for the drug free years: Session-specific effects of a universal parent-training intervention with rural families. J Drug Educ 31(1):47-68, 2001.

-

Miller, T.R., and Hendrie, D. Substance abuse prevention dollars and cents: A cost-benefit analysis. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. Rockville, MD: DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 07-4298, 2009.

-

Moon, D.; Hecht, M.; Jackson, K.; and Spellers, R. Ethnic and gender differences and similarities in adolescent drug use and refusals of drug offers. Subst Use Misuse 34(8):1059-1083, 1999.

-

Oetting, E.; Edwards, R.; Kelly, K.; and Beauvais, F. Risk and protective factors for drug use among rural American youth. In: Robertson, E.B.; Sloboda, Z.; Boyd, G.M.; Beatty, L.; and Kozel, N.J., eds. Rural Substance Abuse: State of Knowledge and Issues. NIDA Research Monograph No. 168. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 90-130, 1997.

-

Olds, D.; Henderson, C.R.; Cole, R.; Eckenrode, J.; Kitzman, H.; Luckey, D.; Pettit, L.; Sidora, K.; Morris, P. and Powers, J. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children's criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280(14):1238-1244, 1998.

-

Pentz, M.A.; Costs, benefits, and cost-effectiveness of comprehensive drug abuse prevention. In: Bukoski, W.J., and Evans, R.I., eds. Cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness research of drug abuse prevention: Implications for programming and policy. NIDA Research Monograph No. 176. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 111-129, 1998.

-

Riggs, N.R.; Greenberg, M.T.; Kusche, C.A.; and Pentz, M.A. The mediational role of neurocognition in the behavioral outcomes of a social-emotional prevention program in elementary school students: Effects of the PATHS curriculum. Prev Sci 7(1):91-102, 2006.

-

Scheier, L.; Botvin, G.; Diaz, T.; and Griffin, K. Social skills, competence, and drug refusal efficacy as predictors of adolescent alcohol use. J Drug Educ 29(3):251-278, 1999.

-

Spoth, R.; Redmond, C.; Shin, C.; and Azevedo, K. Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: School-level growth curve analyses 6 years following baseline. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(3):535-542, 2004.

-

Spoth, R.; Guyull, M.; and Day, S. Universal family-focused interventions in alcohol-use disorder prevention: Cost effectiveness and cost benefit analyses of two interventions. J Stud Alcohol 63:219-228, 2002a.

-

Spoth, R.L.; Redmond, C.; Trudeau, L.; and Shin, C. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychol Addict Behav 16(2):129-134, 2002b.

-

Spoth, R.L.; Redmond, C.; Trudeau, L.; and C.S. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychol Addict Behav 16(2):129-134, 2002c.

-

Stormshak, E.A.; Dishion, T.J.; Light, J.; and Yasui, M. Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: linking service delivery to change in student problem behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 33(6):723-733, 2005.

-

Webster-Stratton, C. Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. J Consult Clin Psychol 66:715-730, 1998.

-

Webster-Stratton, C.; Reid, J.; and Hammond, M. Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. J Clin Child Psychol 30:282-302, 2001.

-

Wills, T.; McNamara, G.; Vaccaro, D.; and Hirky, A. Escalated substance use: A longitudinal grouping analysis from early to middle adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 105:166-180, 1996.